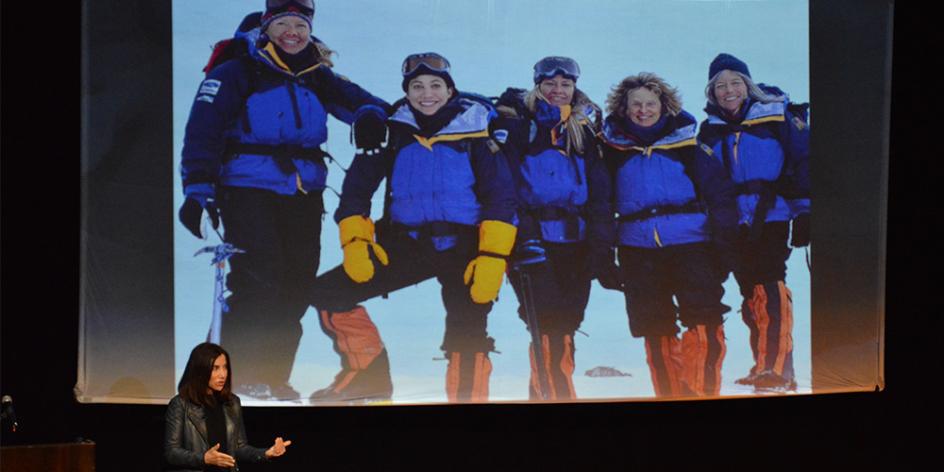

Alison Levine is a renowned mountain climber having scaled the highest peak on every continent and skied across the Arctic Circle to the geographic North Pole. However, before she was able to claim that accomplishment, Levine led the first all-American women’s Mount Everest exhibition team in 2002. She was aware that Everest was going to be the biggest physical and mental challenge a mountaineer could embark on; what she didn’t know was how a giant pile of rock and ice would test her leadership abilities and outlook on life itself.

Levine, the author of “On the Edge,” shared her thrilling and inspiring Everest expedition Wednesday as the second HYPE Career Ready® speaker for the 2021-22 year.

Hidden lessons on the side of a mountain

When presented with the idea of leading the first all-American women’s Mount Everest expedition team in 2002, Levine’s response was “no” because she doubted herself, thinking that she was not good enough, fast enough or strong enough. After she hung up the phone, she pushed that doubt away by reminding herself that there would only be “one first American women’s Everest expedition and if I didn’t step up to the plate to be the team captain somebody else was gonna do it.” She changed her mind and accepted the role of team leader.

“There are times in your life when you just have to step up, even if you don’t know where you’re going,” she said.

After many months of finding a sponsor, gathering a team and attending promotional events, it was time for the team to finally set foot on the mountain. What most people don’t know is that climbing Everest is not a straight shot to the peak. Surprisingly, climbing Everest consists of descending the mountain just as much as ascending the mountain. This is due to the altitude and the health effects it has on the human body if time is not given to adjust.

Base camp is around 17,000 feet and takes the first ten days to hike to it. From there, the climbers spent a couple of nights acclimating. The next step is trudging to Camp 1 to spend the night, then the next day packing up everything and heading back down to base camp to spend another couple of nights there. Then you hike back to camp one to stay the night, then make your way to camp two and stay the night. This process is repeated at each level of camp. This was mentally one of the biggest challenges because Levine and her team had felt as if they weren’t making much progress. But it was actually putting them closer to the peak even as they descended the mountain.

“Backing up is not the same as backing down,” Levine said. “Don’t look at going backward as losing ground. It’s not defeat but an opportunity to gain strength so you’re better the next time.”

Along Levine’s journey, the feeling of fear was a constant emotion. There were enormous ice chunks moving and small rickety aluminum ladders used to cross crevasses with the dropoff of thousands of feet. This is where Levine learned how to use her fear to her advantage and not let it control her. She found that her fear kept her alert and aware of everything going on around her.

“Fear is OK. It’s a normal human emotion. Complacency is what will kill you,” she said.

When climbing Mount Everest, unexpected and uncontrollable events can throw off the plan, the weather being the biggest uncertainty. One moment the summit is surrounded by blue sky with the sun shining on it and the next moment clouds have gathered around it shutting everything else out. “But the one thing you know about these storms is that they’re always temporary,” she said, citing an analogy to real life.

“You survive these storms by adjusting to the situation and not sticking to some plan. While it’s good to have a plan, the environment on the mountain can change quickly. This pertains to life as well, we all go through storms. But we have to remind ourselves that it’s temporary and that maybe what we had planned isn’t the best course of action.”

Levine knows this very well. As she and her team were approaching the summit -- just 270 feet away -- a storm suddenly rolled in. Between the pace they were going and the extreme altitude, they were forced to turn around and descend Mount Everest for the last time. While it had been disappointing for the team to not quite make the peak, they still managed to climb the mountain, but not everyone agreed when they returned.

Coming out on top

Upon returning home, the media wanted to know about the expedition. When Levine told their story, it was met with skeptical comments such as “Well, you really didn’t climb the mountain then” or “How does it feel to fail”? Yet, Levine didn’t feel as if the team failed. Was it disappointing? Yes, but they did surpass many obstacles time and time again. She was more than satisfied with the expedition.

After Levine’s experience with Mount Everest, she never thought she would be traveling up into that mountain again. The only way she would go would be if her best friend Meg joined her. She had hiked the largest mountain in the world and not making it to the top wasn’t a major concern. A few years later Meg passed away due to health problems. She was a well-known athlete, thus people and events were honoring Meg. Levine decided she’d honor Meg in reclimbing Mount Everest. With Meg’s name etched into her icepick, Levine again tackled Mount Everest, and this time, she made it all the way to the summit. It was a personal accomplishment, but she found it anticlimactic.

“Honestly, it just wasn’t that big a deal. Maybe it was the highest mountain, but it’s still just a pile of rock and ice. It’s not going to change the world. … What will change the world is technology, innovation, health care, raising kind, compassionate children, being a good pet parent.”

Biggest takeaway

Levine told the students to remember this: “You don’t have to be the best, fastest, strongest climber. You just have to be relentless in putting one foot in front of the other. That’s how you get to the top of the mountain.”

By Bailey Walter, '23