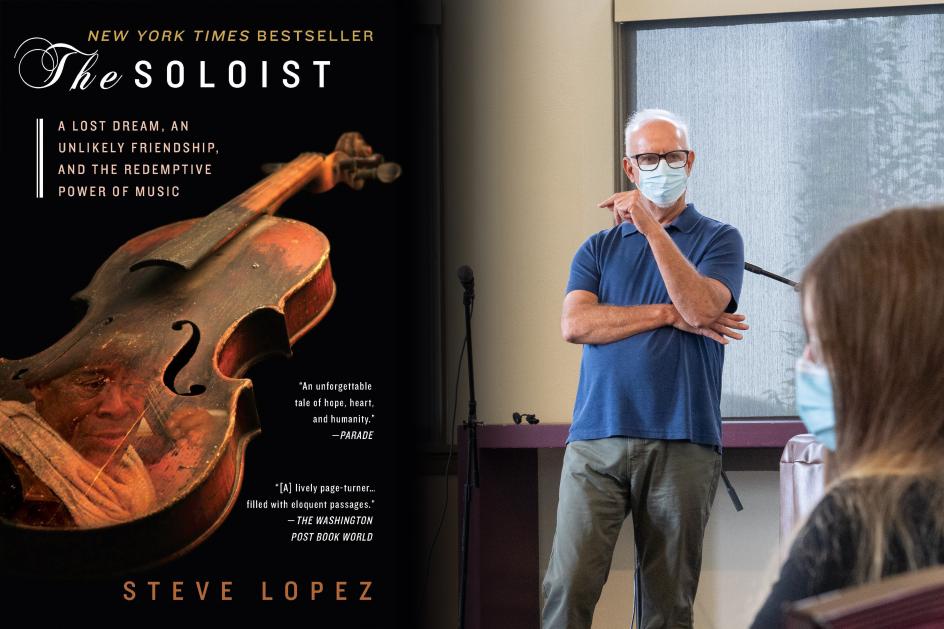

Students in Dr. Sarah Lazzari’s Contemporary U.S. Social Issues class have been discussing some heavy issues this semester: homelessness, racism, addiction and mental illness. Part of their class is reading The Soloist: A Lost Dream, an Unlikely Friendship and the Redemptive Power of Music.

On Tuesday, the class got to meet the author, Scott Lopez, who came to campus to share his experiences befriending and writing about Juilliard-trained musician Nathaniel Ayers, who he encountered playing a two-string violin on Los Angeles’ skid row.

“While many of us are either personally impacted or know of someone who is impacted by these major issues, for some of us, these might be some of the first conversations we’re having about them,” Sarah said. “Mr. Lopez brought these issues to life for the students.”

“He was able to share first-hand accounts of the struggles he has endured and continues to endure as he accompanies his friend who deals with mental illness,” she added.

The author’s odyssey began 30 years ago when he was working as a journalist, simply looking for his next column. “I was in downtown L.A. when I heard music. I turned to find a man playing a violin with two strings, living from a shopping cart,” he recalled. His first reaction wasn’t to help but to find a way to write about the man.

He found it impossible to walk away. Nathaniel, though, was suspicious, didn’t want to talk. This once-promising classical bass student at Juilliard – one of the few African Americans there – had gradually lost his ability to function, overcome by schizophrenia.

Lopez didn’t give up.

Initially hesitant to write about Nathaniel, Lopez saw it as an opportunity to begin to address the stigma that often accompanies mental illness. “I wanted to embrace the opportunity to humanize the issue of homelessness,” he told the ‘Berg students, “and to begin to navigate the severely under-sourced mental health system.”

Eventually, Nathaniel became more trusting, and the two became more than journalist and homeless man; they became friends and remain so today.

“One of the things I love most about Nathaniel is there’s no self-pity,” Lopez said. “He was never bitter, still isn’t.”

Nathaniel taught the author a great lesson about passion. Lopez had considered getting out of the journalism business, but seeing his friend on a milk crate, playing his cello, “he was just in ecstacy.”

“I said to him, ‘You have something you love.’ And his response was, ‘So do you. You get to tell stories.’”

Nathaniel’s greatest gifts were his purpose and passion, and especially, his humility.

That same lesson can be applied to students in college, seeking to find their purpose and passion, Lopez said. “Some never find it. Nathaniel found his.”

Lopez also learned a great deal about mental health care, illness and policies. He learned there is no cure but there is a concept called recovery.

“We have come to accept that it’s OK for someone with mental health issues to sleep in a gutter,” Lopez said, noting that different standards apply to conditions without the stigma of mental illness.

Throughout the class, Lopez answered questions about his relationship with Nathaniel, his personal knowledge of the shortcomings of the complex mental health system, the making of his book into a movie, and the status of life today for both of them.

In response to a student’s question, Lopez told the class that when they “hear someone spouting about bums and addicts, step in and say, ‘Hey, let me tell you a story (if you know someone with mental illness), and don’t just accept ignorance.”

Sarah hopes the author’s first-hand accounts infused a dose of reality – and maybe even passion and purpose – for the students when they contemplate issues of homelessness and mental illness.

“He became real for them,” she said. “My hope is that this may light a fire or ignite a passion for the advocacy that Mr. Lopez suggests is important in changing the way we respond to mental illness.”